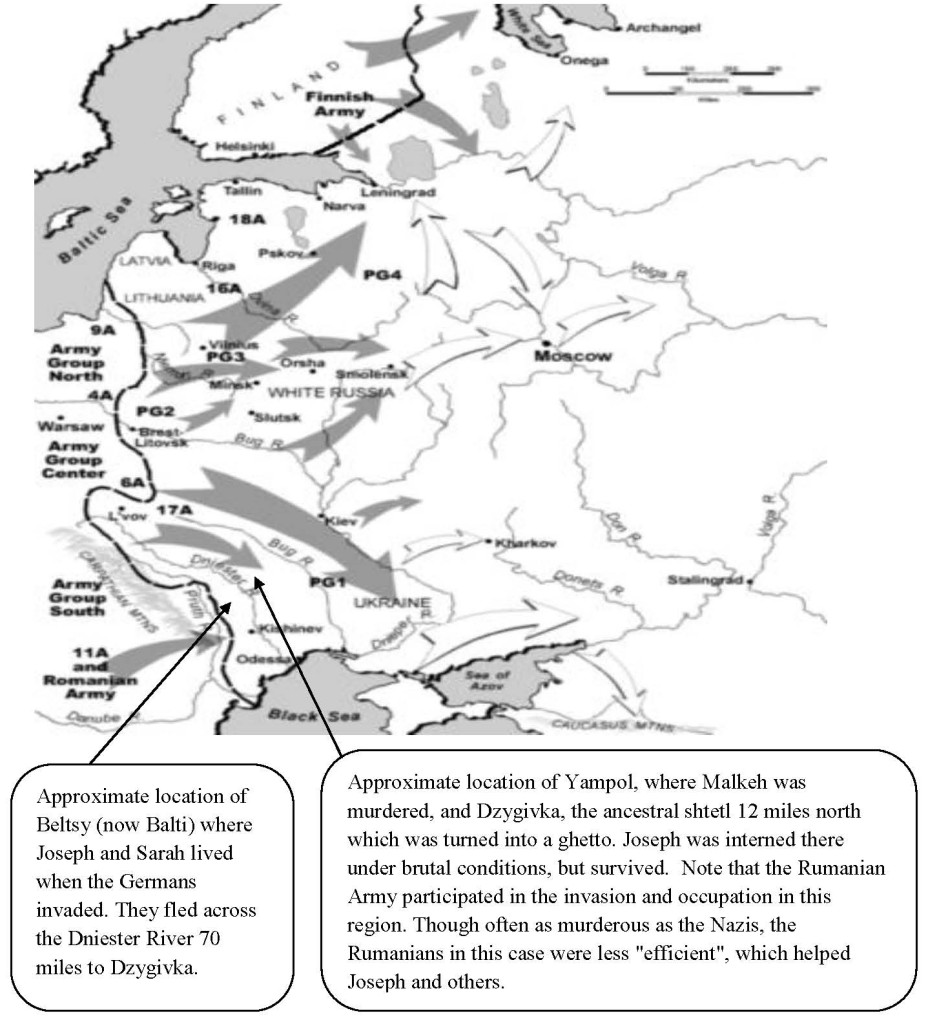

The German invasion of the Soviet Union began June 22, 1941. Of the seven children of Solomon and Perel, two were safe in North America, David and Esther. Goldeh had died in childbirth in 1918. The remaining four were in mortal peril: Malkeh, who lived near Dzygivka in Yampol, Ukraine; Joseph, who lived in Beltsy, then part of Rumania; Elkeh, who lived in Chernigov, Ukraine; and Malieh, who lived in Monastyrishche, Ukraine.

Solomon himself had died in 1939, in Dzygivka. Perel had been able to move to Beltsy to live with Joseph. She died there in 1940.

[Ironically, Perel could go to Joseph because the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939—the so-called non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Bolshevik Soviet Union which stunned the world—permitted Germany to invade Poland from the west while the Soviet Union invaded from the east, simultaneously biting off the part of Rumania where Joseph lived and integrating it into the Soviet Union.]

The German invasion was preceded by massive aerial bombardment. Various army groups swiftly moved east, following the German war strategy of lightning advance: “blitzkrieg”. Rumania, an ally of the Nazis, participated in the invasion and occupation of the Soviet Union in the far south of the front line.

The Holocaust began immediately. While the infamous death camps were yet to come into existence in Poland, the Nazis and their allies perpetrated mass slaughter (the “Holocaust by Bullet”) wherever they went. Concentration camps, ghettos, were set up where tens of thousands died from starvation or disease.

The only possible way to escape the German onslaught was to flee eastward into the vast interior of the Soviet Union. Thanks to the heroic effort of Melech Perelroisen, this is what his wife Elkeh and sister-in-law Malieh were able to do. Joseph and Malkeh were trapped. Joseph survived, barely, along with his wife Sarah and daughter Ida. Malkeh did not.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union, June 22, 1941

What we know about the family comes from the letters of Amnon, Joseph’s son, from Mike’s 1996 visit, in which he was able to gather additional information from Amnon, who in the war was in the Red Army; from Ida, Amnon’s sister, who was interned in Dzygivka and who in 1997 provided testimony about her experiences; and from Fanya, daughter of Elkeh, who had fled to the east. All three of these witnesses have now passed away.

A separate narrative of survival can be found in Fima’s Story.

From Mike’s journal and Amnon’s February 1990 letter:

[Journal] I ask Amnon for details about what happened to our family during World War II. (He had written about the war in his letters…)

Joseph and Sarah lived in Beltsy when the war began in June, 1941. Beltsy was subjected to devastating German bombardment as the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, backed by their Rumanian allies. This was the southernmost of the three fronts upon which the Germans attacked.

Joseph, who was then 56 years old, fled eastward with his wife and daughter, Ida. [She was 20 years old.] (Amnon, then 28, had already joined the army.) When Sarah suffered heat exhaustion, the family decided to head for Dzygovka, 50 miles east of Beltsy. They knew relatives of Pearl, Joseph’s mother, were still living there.

[Letter] In one of the first days of the war during a mass air attack of the German bombardment Beltsy was reduced to ruins and our house was also razed to the ground. Luckily, when the raid took place my parents and my sister were out of town in their vineyard. I lived in Kishinev then and was mobilized for defensive work.

So in the next day my father harnessed his horse, and the small family went towards east. Three day later, as soon as they reached the river Dniester, they suddenly heard the specific drone of German bombing aircraft that became louder and louder. They hid under a big branchy tree and in a few moments they saw the bridge over the river blowing up. At last a great distance away from that place they crossed the river on a military ferry-boat and continued their route.

Unfortunately my mother got a sun-stroke on the way and my father decided to go towards Dzigovka and to wait there until she recovers. In Dzigovka they met the Balabans who had come there from Jampol that is located on the left bank of the Dniester. But soon Jampol, Dzigovka and many other localities of that region were occupied by Nazi forces. Since Dzigovka was a village of no strategic importance only a dozen of Rumanian soldiers and their commanding officer were sent there to establish the “new order”.

So our family birthplace became a ghetto with all its restrictions and severe rules that the Jews had to follow. Some of them died of dystrophy owing to malnutrition, others for lack of medical aid and medicaments. But no one was murdered there by the Rumanians because the commanding officer proved to be not so cruel as others were (in other Jewish ghettos of Ukraine).

[Journal] They reached Dzygovka safely and spent the war there, interned by a Rumanian detachment which turned the village into a Jewish ghetto. Remarkably, compared to what happened elsewhere, this particular Rumanian unit did not kill Jews.

Amnon says the only time he ever saw Dzygovka was after it was liberated by the Red Army in May, 1944. He was an officer in intelligence, the head of his unit, and was able to get to the village to search for his parents. He found them in pathetically weak condition but alive, and was able to get them out, first to Soroki and then to Kishinev after it was liberated in August, 1944.

Amnon’s account is reflected in modern historical research. Here is a description in Lucy Dawidowicz’ The War Against the Jews, 1933-1945:

In Bessarabia, over 200,000 Rumanian army units working with Einsatzgruppen D in southern Russia dismayed the Germans with their passion for killing and their disregard for disposal of the corpses.

In August 1941 the Rumanians began to expel Bessarabian Jews across the Dniester, in territory under German military occupation. The Germans resisted having this area become a dumping ground for unwanted Jews, but then agreed that Transnistria, the area between the Dniester and the Bug rivers, could serve as a reservation for Rumanian Jews.

By mid-November 1941 over 120,000 Jews had been deported there, and by late 1942, according to a conservative estimate, some 200,000 Rumanian Jews had been shipped to Transnistria, nearly two-thirds of whom had already died of hunger and epidemics.

By September 1943, only some 50,000 Rumanian Jews remained alive in Transnistria, along with 25,000 to 30,000 Russian Jews, native inhabitants of that area.

[From the journal] After lunch, I asked Ida her memories of the war. She was in the Dzygovka ghetto with Joseph and Sarah, her mother and father. She remembered the Rumanian commandant as an old man who didn’t want trouble, and who didn’t need to impress the Germans by killing Jews. Dzygovka was a small, out-of-the-way place. The current nearby highway hadn’t been built. The railway was some miles away. The village’s remoteness and obscurity saved the Jewish inhabitants if they did not venture beyond the ghetto walls.

Because Dzygovka was a relatively “safe” ghetto, thousands of Jews sought refuge there. Four or five families would live in a single small house. Ida and her parents lived with Hersh, brother of Joseph’s [actually Amnon’s] grandmother.

Ida remembers an old woman in Dzygovka who told her that a great rabbi once lived in the town, and that he had prophesied no harm would come to Jews there.

In her 1997 testimony, Ida provided many details about her captivity in Dzygovka. Her testimony differs in some respects from Amnon’s recollections. For example, Ida says that Malkeh was shot. Amnon’s version is she was clubbed to death.

Malkeh’s terrible end is related in Amnon’s February, 1990 letter:

Malkeh wasn’t murdered within the bounds of the ghetto but outside it. This is how it happened:

In one summer morning of 1942 Malkeh and two of her friends disguised as peasant women ventured to go out of the ghetto and to make their way towards Jampol in order to get some of their clothes and other things they had left there in the previous year, and then to change them for some food-stuffs.

But they had scarcely walked a few kilometers away from Dzigovka when several Nazi soldiers on motor-cycles appeared on the crossroad. Catching sight of the women, they stopped and using foul language made them signs to come nearer. The frightened women started scattering, and the Nazis that dashed after them managed to catch only Malkeh and another woman. The third one hid in the deep ditch overgrown with shrubs.

The laughter and the cries of the Nazis “Youdehkaput!” [Jude kaput, finish the Jews] reached her ears, and when she heard the horrific shrieks of their victims, the woman fainted. When some time later she came to herself and climbed out of the ditch she found the dead bodies of her unfortunate companions on the side of the road. their faces were mutilated and blood-stained, their sculls were fractured. The monsters of cruelty spared even two of their bullets to kill the Jewish women and murdered them with the butts of their guns.

When the woman who had survived brought the grievous news to Dzigovka, Elly Balaban tore his hair and sobbed for sorrow without pause. The day before the terrible tragedy took place Elly and my father had forewarned Malkeh about the danger. They implored her to put out of her head her intention of going to Jampol. But unfortunately, she was fated to stand on her ground.

I was told the tragic story by my parents when I met them soon after their liberation from the ghetto in April, 1944. Some months later the Soviet forces drove the Nazi occupants out from Moldavia, too and my military unit was transferred to Kishinev. So my father and the others decided to move to this town.

In the meantime we got to know that no one of our 26 relatives from mother’s side had survived. I can’t help telling you in what a barbarous and sadistic way some of them were murdered.

In the first days of the Nazi invasion one of my mother’s sisters and her large family together with other Jews were driven in to an old synagogue. Then the synagogue was set on fire, and all who were inside burned alive.

The Nazi monsters caught two of my cousins and their wives, tied them one to another with a rope and threw them into a deep lake.

Such atrocities and other innumerable heinous crimes that cannibals of the 20th century committed during the holocaust must never be forgotten and never be repeated.

In the journal, Fanya, daughter of Elkeh, tells about herself, her mother and Malieh during the war:

She…went to Kiev to study in a medical training institute. When the war broke out, and the Germans invaded, the institute relocated itself further east, to Kharkov. This was not remote enough, however, and after two months it moved to Chelyabinsk. At the same time, a second institute relocated from Kharkov to the city of Frunze, Kirghizia. This would turn out to be where Fanya would finish, after which she was inducted into the army, as a doctor.

We talk about how her family and the family of Solomon and Manya Rosenberg were able to escape the invading German armies.

Manya Rosenberg and her children, Lidia and Danya, were in Monastarische, closer to the front line, when the war broke out. (Solomon had already joined the army.) The family fled, in a harrowing journey, to Chernigov, where they joined the Pearlroisens. Manya was exhausted by the trip, and said she did not want to go further, but Chernigov soon was threatened.

Melech Pearlroisen saw the danger, swept the tired Manya up, and took her and her family to the Desna River, which flows through Chernigov. He put the Rosenbergs on a boat, along with his wife, Elkeh and daughter Dora. He stayed behind, telling his family he would find them wherever they would be relocated.

The boat went down the Desna to the Dnieper. It safely reached a place where the families were able to register with the authorities and be moved a further east. The Soviet Union had a well-established system for moving not only people but whole factories to the east, beyond the reach of the invading armies.

Elkeh was able to send Fanya a postcard saying the family had been relocated in Tambov province, 200 miles southeast of Moscow. The card brought joy to Fanya, who at the time was in Kharkov, and, having heard that the Germans had occupied Chernigov, was mourning the likelihood her entire family had been wiped out.

Because the postcard said Melech had not joined them, Fanya was concerned for her mother. So she left Kharkov to go to Tambov province, where she found her mother working in a train station in a little village. Life was very difficult.

Meanwhile, Melech had evaded the German invasion, and had somehow found where the family was in Tambov province and went there. He was given work in the town of Tambov. Melech was a bookkeeper.

“My father wrote a letter to every village” in Tambov province, Fanya recalls. He finally found out where they were living, and was reunited with them.

Melech was concerned with the climate, the difficulty of finding work, and with Fanya’s leaving medical school. So he decided the family would move again. The family went to Frunze, in the state of Kirghizia [Frunze was the Bolshevik name for the city, which is the capital. In 1991 the name was changed back to the traditional Bishkek.]. Melech could not find work in that town, so had to move to another in Kirghizia. But Fanya was able to resume her studies in the medical institute which has relocated there from Kharkov.

The Rosenbergs also went to Kirghizia. It was there that Solomon, who was in the army, was able to locate them and be reunited with them.

After the war, Melech and Elkeh returned to Chernigov, as did Manya and her children. Solomon, however remained in the army for two or three years after the end of the war, rising to the rank of Lt. Colonel. When he returned to civilian life, he moved with the family to Odessa.

As I reread these accounts today (Feb. 27, 2014), I marvel at the foresight and swift decisions made by Melech, who saved two Maidenberg sisters.

***

I mourn for Malkeh, and for her daughter Rukhel. Rukhel was described by Amnon (May, 1996) as “an unfortunate girl” who didn’t understand anything, and who never learned to speak. The symptoms he describes are similar to autism. Amnon believes Rukhel died of typhus in the Dzigovka ghetto, rather than being killed with her mother at Jampol. I mourn also for Malkeh’s husband Eliyahu Balaban, who died of either starvation or typhus at another concentration camp, Ladyzhin, not far from Dzigivka.