PHOTO GALLERY

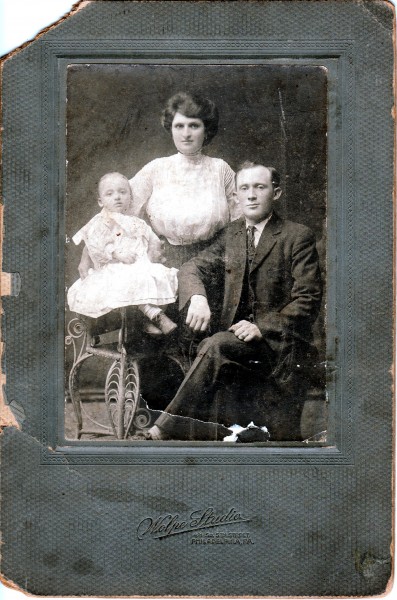

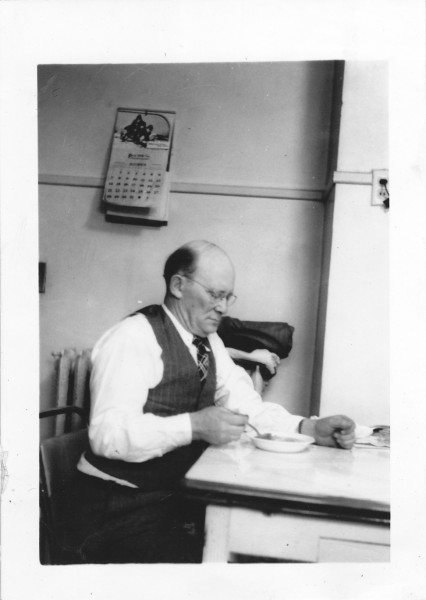

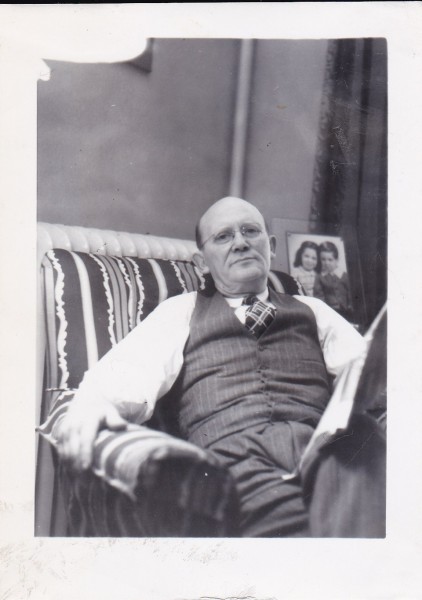

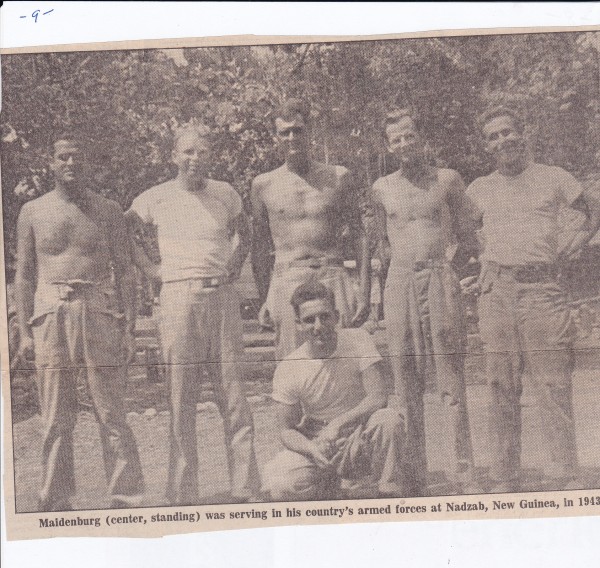

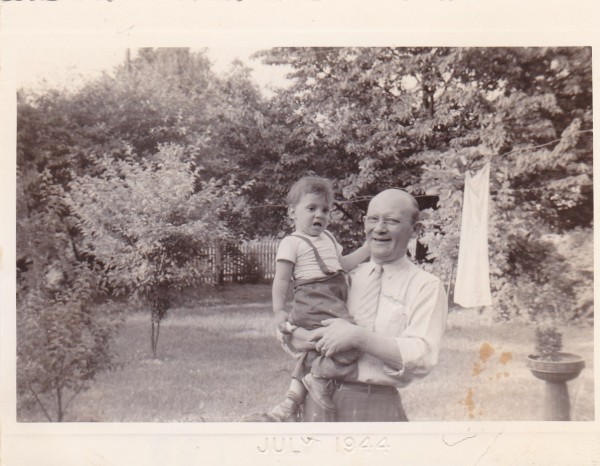

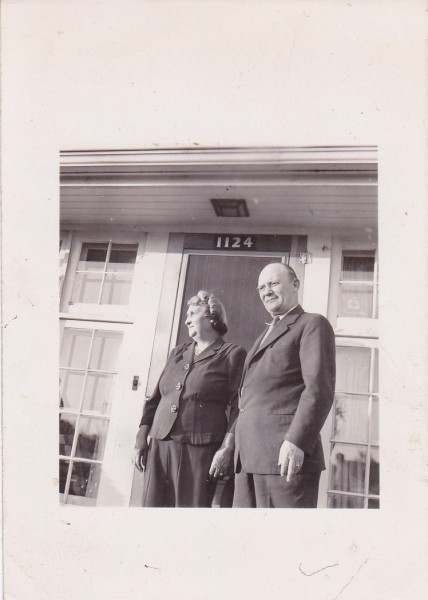

David Maidenberg and Rosa Vinokur

We know only fragments of David’s and Rosa’s lives in Russia before they emigrated to America in 1906.

We do know they left the shtetls of their birth, and moved to Odessa, where they met and married.

One account has David working in a bakery, another as a fruit salesman. His decision to leave is attributed to the 1905 pogrom in Odessa, and also to avoid serving in the Tsar’s army.

In his July 28, 1968 letter to Milt, David’s younger brother Joseph writes:

On the 19th of July I attended the synagogue where I organized a commemoration prayer [clearly a yahrzeit—David died on July 25] to pay due honor to Dave.

I recalled him as a child of 8-10 when we learned and played pranks at the kheder (a Jewish religious primary school) then at the age of 19-20 when he worked in Odessa at a bakery business and took me and my sister Olya [Elkeh] there to continue our studies. (In those times Odessa was not only a center of eminent thinkers, writers, artists, actors and musicians but also a well known center of gangsters, thieves and vagabonds.)

Strong, handsome, energetic and fearless, Dave had always a kind smile on his lips. His job was to deliver bread to different shops and to collect money for it.

I remembered a true story which characterizes your father’s nature when he was in Reed’s age [i.e. 20 years old].

One night returning from school I met Dave on his way home after work, and he took me on his van. Suddenly when we turned up in a dark lane, four bandits stopped the horses, and threatening Dave with daggers and knives proposed him to give them up his day receipts.

Dave pretended that we was ready to obey their order and calmly descended the carriage raising his hands up. A surprise kick followed. One of the bandits fell down and his dagger was in Dave’s hand. Then another heavy blow-and another thief was knocked down. The gangsters ran away.

Next day they came to Dave and invited him to a drinking bout. I was in terror when he told me about it, and I implored him to refuse their invitation. But Dave as usual smiled kindly and said that there is nothing to fear. And really the conquered bandits did him no harm and stood a treat to him for his courage, fearlessness and heavy blows. There are no more such humane bandits nowadays.

Like most of the Maidenbergs David was a very good hearted young man then and could not tolerate injustice. After the 1905 Jewish pogroms in Tzarist Russia he left for the USA together with your mother Rosa.

Amnon, in an interview with Mike in May, 1996, remembers David sending Joseph a kosher-for-Pesach package after the end of WWII.

Over the years David sent back money to his parents. In 1928, he sent 500 rubles for the wedding of his youngest sister, Malieh or Manya.

In the 1930’s David sent his brother Joseph funds to come to America. Joseph chose to stay—but did not send back the money, evidently causing a rift in the relationship that was never fully repaired.

According to Rose’s application for citizenship, she was born in “Roshkiff, Podolska,” which is Rashkov, in the province of Podolia. Her father was Mayer Vinokur, born in 1849 in Rashkov, died before 1900. Her mother, named Fanny, date of birth unknown, died in 1895.

The name “Vinokur” or “wine-maker” suggests an historic family occupation of distilling spirits, a common line of work for Jews at the time.

In his letter of May 18, 1969, Joseph writes:

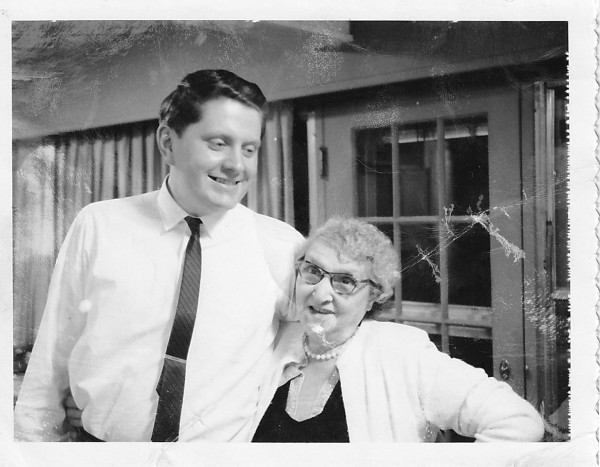

I remember Rose as a very handsome girl of about 20 your father fell in love with. Although Rose was from a very poor family, she was a willful nature in her own way, and only David with his steadiness, with his kind, golden, and tender heart could easily calm her temper. I m sure that being his life satellite for about half a century she adopted at least half his virtues.

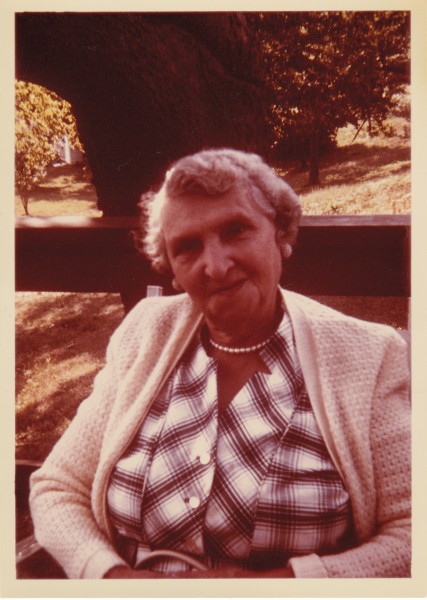

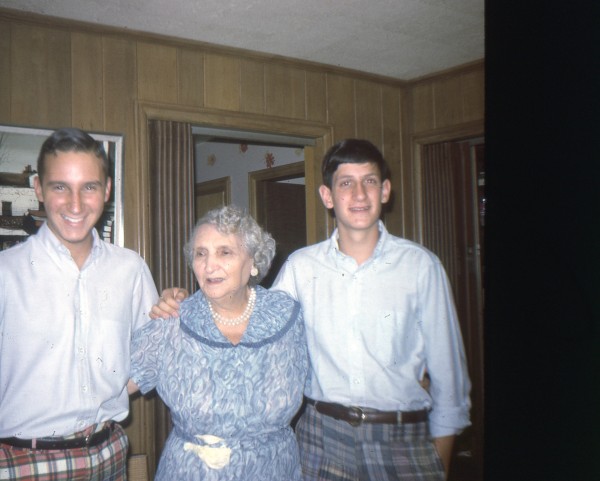

They came to the U.S. with nothing but their hands and restless hearts. Life was not a blazed trail to them. Rose did her best to help David to find a situation, lay up a fortune, to grow up four sons, and give them a start in life. Without doubt she had a fondness not only for herring and homemade soup, and disliked taking advice from ‘squirts’ as she named 60-years-old-doctors, but she also was devoted heart and soul to her 11 grandchildren and two grand-grand-children, worried about their health, happiness, and future, worried about what is going on in the world, admired brave people, their deeds, and disliked unfairness, etc.

Phyllis Wolberg, Rosa’s niece, wrote Jill Maidenberg on Nov. 2, 1983 about David and Rose. Excerpts:

Aunt Rose was one of six children born in a little shtetl in southern Russia– there were five girls in the family and one boy–my father. My father married my mother after serving in the infantry for 5 years and moved to the big city, Odessa, where we children were all born.

Aunt Rose was orphaned when she was 13 or 14 and came to Odessa to stay with her brother. Subsequently she worked for him in one of the stores that both my parents owned. The stores consisted of Persian rugs, Swiss curtains and rare objects. Aunt Rose became a sales person. Lest I forget she had no education whatsoever but what she had was brains, ambitions and determination to get ahead somehow. Jews were not permitted to go to school in those days.

She had one thing in her favor–as my mother told me–she was a very beautiful woman with a personality that attracted many young men to her.

My mother met Uncle David and decided that he would make a good husband for Rose. So he was invited to our home. When Rose saw this handsome young man with blond hair, blue eyes and above all beautiful manners, she succumbed.

He fell in love with her forthwith and shortly thereafter to avoid joining the army the two married and left for America. They went to Philadelphia where

David’s aunt lived. Uncle David had no skills. He was a fruit salesman in Odessa. So he decided to become a peddler, going from town to town. Aunt Rose stayed in Philadelphia and then I don’t know why they moved to Hagerstown, Maryland, where Meyer was born.

This excerpt from Phyllis is about Rosa’s life in Marion.

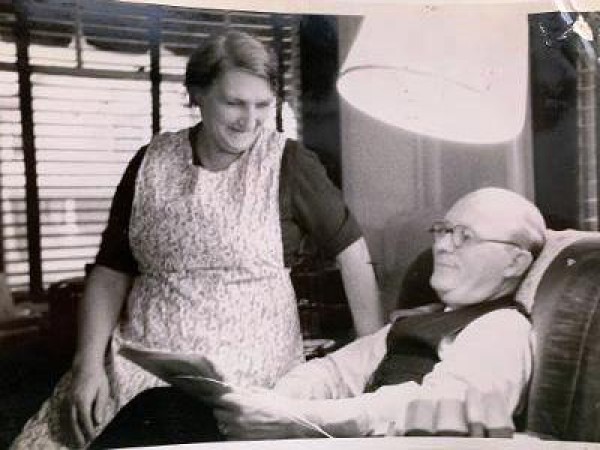

Your grandmother had a great struggle to make ends meet. My, she was a great worker. She cooked, she cleaned, she took care of the house, the children, the garden and what not.

And when Uncle David came home at night the table was set, the children were washed and waiting at table to eat with their Daddy.

Yes, Jill, Aunt Rose had a reputation in Marion of being stingy– but if you look into her background you can see why. Every penny meant something to her.

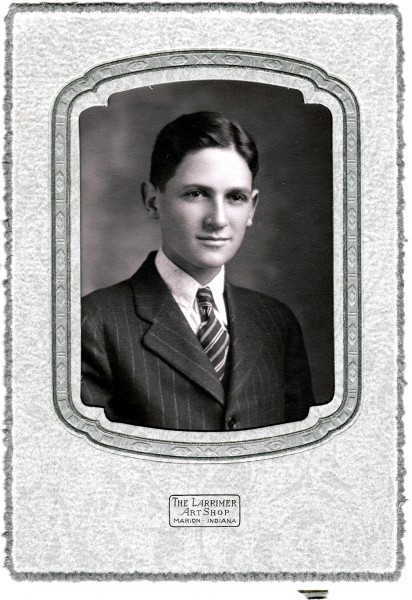

She was all for her family . When Milton went to college he sent his laundry home for his mother to take care of. When Frank your father was out of high school he decided against further schooling. He wanted a career- so he went to some place in Pennsylvania, bought glassware and dishes and whatnot. His mother stayed up nights washing everything and helping him to arrange his wares so that he could start selling before Christmas.

She was devoted and unselfish and what a worker. You can be proud if you have any of her genes. Her great obstacle of course was a lack of education. It that woman had had that she would have risen to great heights. She was a lady of great character. We all loved and admired her.

In an oral interview [add link] Frank Maidenberg provided detail about his parents.

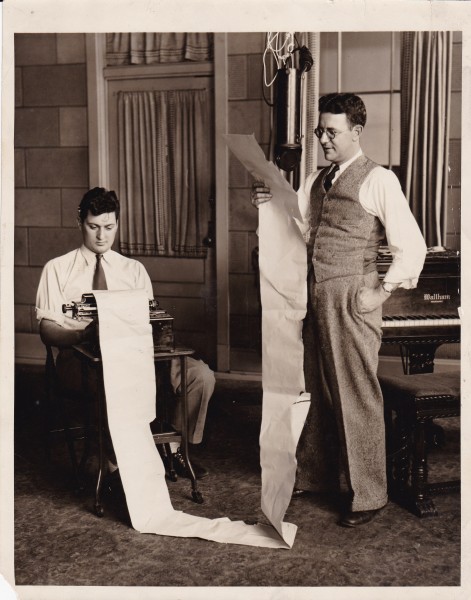

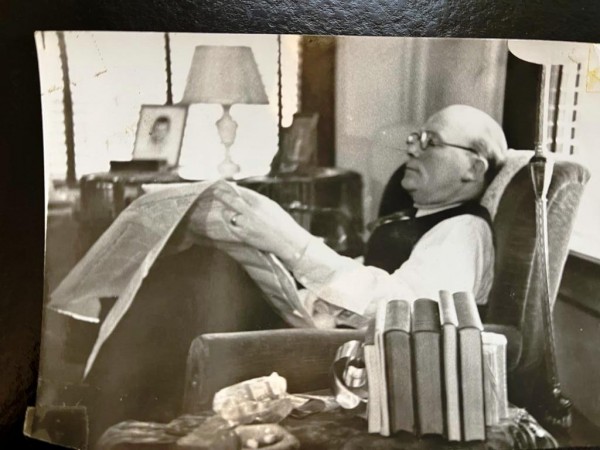

Pop was a very good student. He learned to speak English, wanted his children to be forced to learn English. When he came home from the store in Gas City he would read the Yiddish newspaper, Der Tog, and also the local newspaper.

He kept his books in Hebrew writing. Befuddled an IRS examination.

Pop was very bright, spoke understandable English. He had a fantastic memory. All of his customers when they would come into the store, he knew their families, asked about them, by name.

Mom and Pop always spoke Yiddish at home. We spoke English. When Mom and Pop wanted to talk in private, they used Russian.

He took me with him to Gas City, Upland. We parked, sold off the back of the buggy. Muslin, dress goods, like a farmers market.

No anti-Semitism that affected him in Marion or Gas City.

When [customers] came up to the wagon, Pop would say how is your mother, your daughter, how is so and so doing? Amazing. He called himself “Dovid.”

He opened the dry goods store in Gas City. There was glass factory there that had opened. Indiana Dry Goods store. His suppliers trusted him, helped him stock the store with merchandise.

Pop had a horse and wagon. Horse was Prince. Maybe a touch of what they had in the old country.

They wanted us to go to school. Mom would meet the teacher, ask about us.

Never was a Jewish family in Gas City, nor other places where Pop sold, Sweetser, Upland. Once in a blue moon I would hear Mom and Pop talking about a “bad goy” who disparaged the “Jew peddler.”

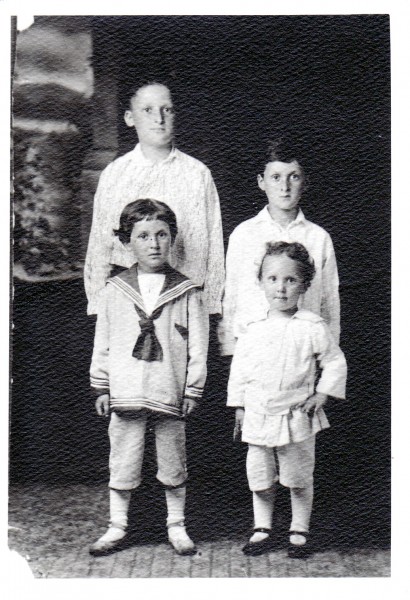

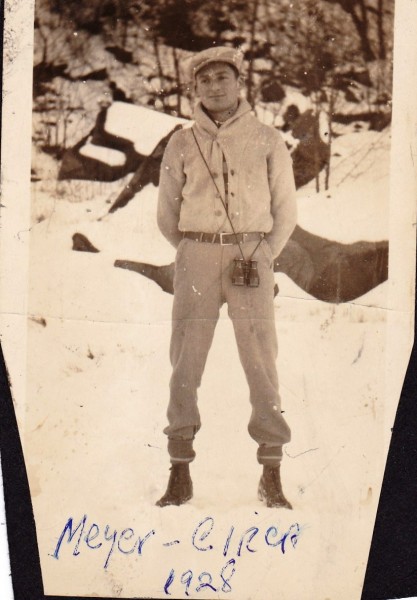

We all had pet names. Milt had a lisp, small speech impediment, we called him the shtimmer-kutter. I was called the stinker because I would forget to go to the toilet sometimes. Ben was Bentsy tsvok, Benny the Nail. He was the athlete in the family. Meyer was the pisher, because he used to wet the bed.

[Yiddish: “shtinker” for stinker; “shtimmer-kutter”, literally “mute cat” meaning speech-impaired; “tsvok” or “tchvok” for nail. “Pisher” is self-explanatory.]

Pop, well the older boys didn’t have as much contact, communication with him as I did. I was lucky. He wasn’t consumed with always making a living. He would talk with me about business, about how he came to the wrong Marion, other things. He had a good outlook on life. He was good at business, and with customers. He was amazing in the way he educated himself.

Mom made a dish called veranikas and another called zoverin russel, both of them full of fat.

Mom always served the chicken soup at the end of the meal to “wash everything down.” It had knedlach. It was too much.

I had long talks with him on the porch. He was quite upset that his neighbors in the old country overnight would become enemies because of the edict of the Czar. Pop basically trusted people though. He helped them and they him. He kept his head above prejudice. I’m sure he changed a lot of anti-Semites’ minds.

We had an orthodox shul in Marion. He was president. We didn’t have a rabbi, although we had a shochet who came to town to kill chickens. The schochet would teach the kids Hebrew, for their bar mitzvah. But I wanted to know what the Hebrew meant, and the shochet got annoyed with me.

Pop was a leader, but he helped get the Reform congregation started, so the kids would not get detached from religion.

Pop liked to have people over for political debate. He liked to travel, more than Mom, who was fixed in her habits. He visited Esther in Canada. He liked people and liked to talk to people.

Mom would sometimes talk of the chazerish goyim, but she made many good friends. They weren’t prejudiced.

Mom was hard working. Devoted to the family. She would chew food for us when we were little and there was no baby food.

She was a bright lady, but without an education.

We had a strictly kosher home, different sets of dishes, special ones for Passover. I remember all the work we went through on Passover putting some sets away, unwrapping the Passover plates. Those were their customs.

Mom would bake extra bread for non-Jewish friends, also strudel, gefilte fish, which had to be ground, not chopped.

Seders in our home always lasted too long. Pop was very traditional. We didn’t understand what he was saying.

We would build a sukkah. Meyer made the frame. We would hang corn.

We never had a Christmas tree. We talked about it. Sometimes a new family would come to town and put up a tree. This caused a lot of discussion among the old-timers. How can there be a Christmas tree in a Jewish home?

The Depression was horrible. We were still fighting it when World War II started. That’s what pulled us out.

During the Depression my father struggled along. He lost a lot of money. People couldn’t pay their bills. He had to borrow money at high rates.

Pop fortunately held his own. He remembered barter, let people pay him in kind. He pulled out of it, but it was touch and go.